|

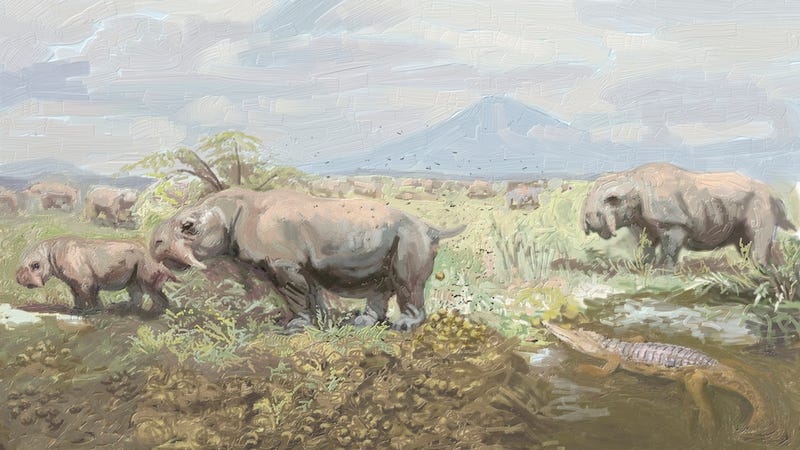

| Artistic recreation of the ancient reptiles, dicynodonts, using their communal latrine. Courtesy of Emilio López Rolandi. |

Communal latrines, or defecation spots, are exactly what they sound like: Relatively small areas where multiple individuals relieve themselves, sometimes at the same time. Humans and housecats obviously defecate in communal latrines, but studies show that a number of other mammals do, too, and the behavior is particularly common among large herbivores.

In fact, research shows this behavior was an ancient evolutionary development: scientists have discovered a large, rhino-like reptile defecated in "communal latrines" some 240 million years ago. Turns out, communal latrines have important biological functions.

The eight communal latrines the researchers discovered were each 400 to 900 square meters and 1.5 kilometers apart. These fields were loaded with fossilized poo called coprolites - within the latrines, there were, on average, 67 coprolites per square meter, but in some areas the poo density reached 94 coprolites per square meter. Given the amount of coprolites and their size variation, the researchers believe the latrines were really communal, and used by many animals of different ages.

|

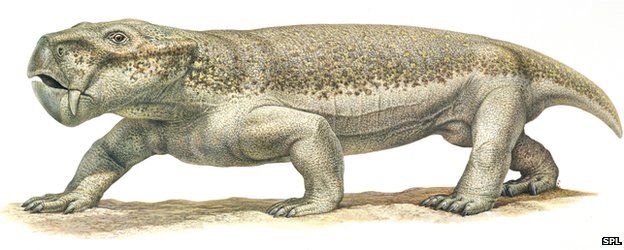

| The culprits were dicynodonts - ancient megaherbivores |

"There is no doubt who the culprit was," said Dr Lucas Fiorelli, of Crilar-Conicet, who discovered the dung heaps. The perpetrator was Dinodontosaurus, an eight-foot-long megaherbivore similar to modern rhinos. These animals were dicynodonts - large, mammal-like reptiles common in the Triassic period when the first dinosaurs began to emerge. The fact they shared latrines suggests they were gregarious, herd animals, who had good reasons to poo strategically, said Dr Fiorelli:

"Firstly, it was important to avoid parasites - 'you don't poo where you eat', as the saying goes.

"But it's also a warning to predators. If you leave a huge pile, you are saying: 'Hey! We are a big herd. Watch out!"

The new discovery also indicates that the seemingly mammal-only behavior of defecating in communal latrines developed before mammals first evolved. This new find actually predates the previous fossil record of communal latrines by 220 million years. We may owe our sanitary practices to our reptile ancestors.

Anyone remember the show Dinosaurs? Here's the episode where the baby runs away to the forest rather than poop in the same place as everyone else, because, as he explains it to the other forest denizens (hereafter FD1 and FD2),..

Baby: They tried to make me go potty.

FD1 explains to the others: When nature calls you've got to go to this one particular room and sit in this special chair...

FD2: You're making this up!

FD1: No, wait, wait wait there's even more conditions than that - everyone uses the same chair!

(loud expressions of disgust)

FD2: But, wait, what if you have to go and someone's already using the chair?

FD1: Then you have to wait.

FD2: But what if you can't wait?

FD1: You have to!

Baby: I wanna go when I wanna go!

FD1: Well, that's how we do it out here. You can go any time you want, anywhere you want.

Baby: Anywhere?

FD2: Well, except over there - that's the volleyball court.

Start watching at 8:50, if the video doesn't automatically start there:

Here's the full scientific article, a report at BBC, and discussion at io9.

Baby: They tried to make me go potty.

FD1 explains to the others: When nature calls you've got to go to this one particular room and sit in this special chair...

FD2: You're making this up!

FD1: No, wait, wait wait there's even more conditions than that - everyone uses the same chair!

(loud expressions of disgust)

FD2: But, wait, what if you have to go and someone's already using the chair?

FD1: Then you have to wait.

FD2: But what if you can't wait?

FD1: You have to!

Baby: I wanna go when I wanna go!

FD1: Well, that's how we do it out here. You can go any time you want, anywhere you want.

Baby: Anywhere?

FD2: Well, except over there - that's the volleyball court.

Start watching at 8:50, if the video doesn't automatically start there:

Here's the full scientific article, a report at BBC, and discussion at io9.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-25126333

ReplyDelete