|

| Poseidon taking chocolate from Mexico to Europe, a detail from the frontispiece to Chocolata Inda by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma, 1644 |

In the seventeenth century, Europeans who had not traveled overseas tasted coffee, hot chocolate, and tea for the very first time. For this brand new clientele, the brews of foreign beans and leaves carried within them the wonder and danger of far-away lands. They were classified at first not as food, but as drugs — pleasant-tasting, with recommended dosages prescribed by pharmacists and physicians, and dangerous when self-administered. As they warmed to the use and abuse of hot beverages, Europeans frequently experienced moral and physical confusion brought on by frothy pungency, unpredictable effects, and even (rumor had it) fatality.

Madame de Sévigné, marquise and diarist of court life, famously cautioned her daughter about chocolate in a letter when its effects still inspired awe tinged with fear: “And what do we make of chocolate? Are you not afraid that it will burn your blood? Could it be that these miraculous effects mask some kind of inferno [in the body]?”

|

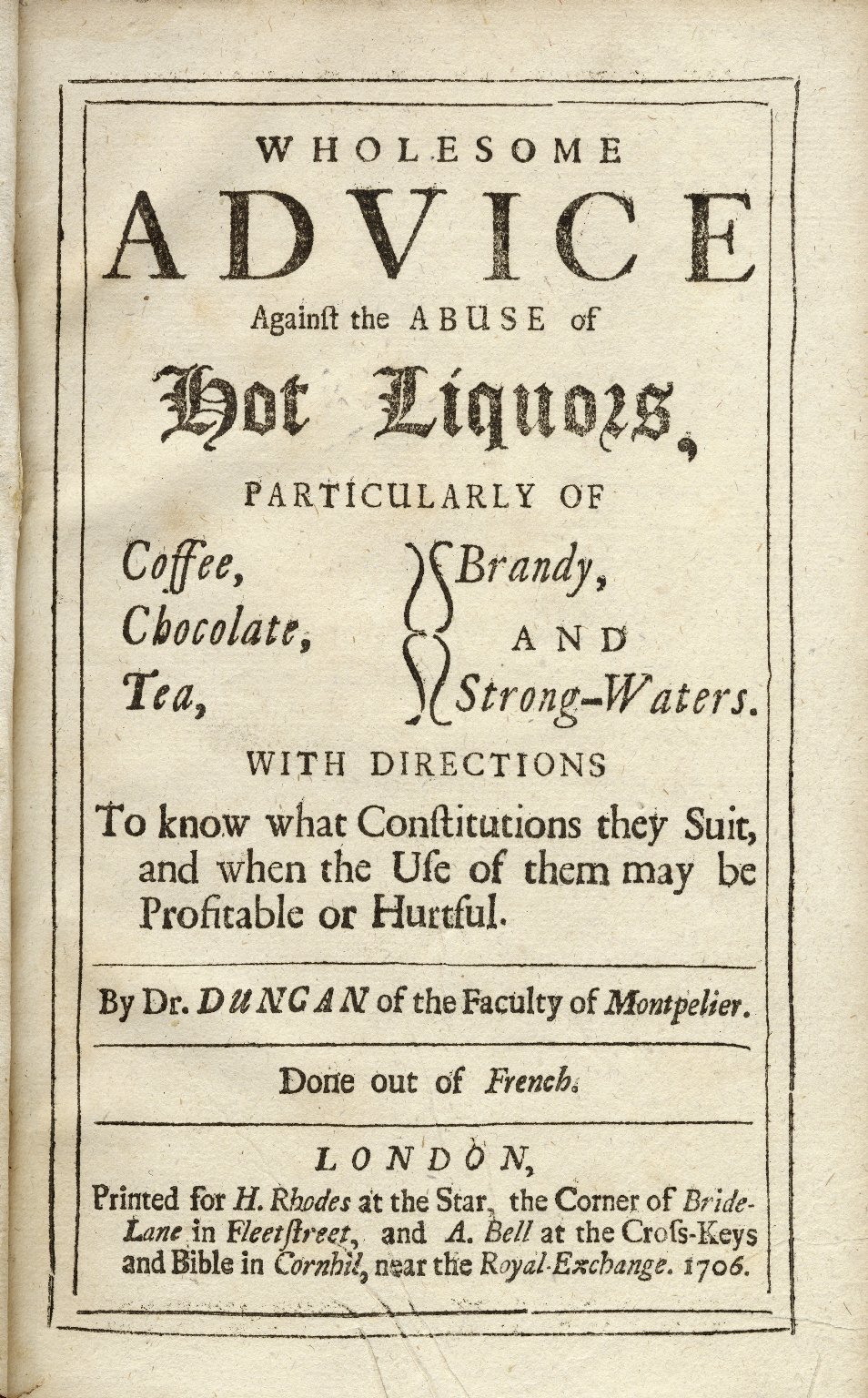

| Title page from Dr Daniel Duncan’s Wholesome advice against the abuse of hot liquors, published in London in 1706 |

Read about humoralism, and much more about chocolate as medicine, in Public Domain Review.These mischievously potent drugs were met with widespread curiosity and concern. In response, a written tradition of treatises was born over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Physicians and tradesmen who claimed knowledge of fields from pharmacology to etiquette proclaimed the many health benefits of hot drinks or issued impassioned warnings about their abuse. The resulting textual tradition documents how the tonics were depicted during the first century of their hotly debated place among Europe’s delicacies.Chocolate was the first of the three to enter the pharmaceutical annals in Europe via a medical essay published in Madrid in 1631: Curioso Tratado de la naturaleza y calidad del chocolate by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma. Colmenero’s short treatise dates from the era when Spain was the main importer of chocolate. Spain had occupied the Aztec territories since the time of Cortés in the 1540s — the first Spanish-language description of chocolate dates from the 1552 — whereas the British and French were only beginning to establish a colonial presence in the Caribbean and South America during the 1620s and 30s. Having acquired a degree in medicine and served a Jesuit mission in the colonies, Colmenero was as close as one could come to a European expert on the pharmaceutical qualities of the cacao bean. Classified as medical literature in libraries today, Colmenero’s work introduced chocolate to Europe as a drug by appealing to the science of the humors, or essential bodily fluids.

Previous related posts:

How to Prevent Pregnancy, c. 1260 (the weasel/scorpion method), plus other dubious medical advice.

Advice from 1380: How to Tell if Someone Is or Is Not Dead, with bonus Monty Python.

The c. 1275 miraculous transplantation of a leg.

Advice from c. 530: How To Use Bacon, including for medicinal purposes such as "thick bacon, placed for a long time on all wounds, be they external or internal or caused by a blow, both cleanses any putrefaction and aids healing".

Advice from 1489: To stay young, suck blood from a youth.

How to Stop Bleeding, 1664:

“To Stench a Bleeding Wound: Lay hogs Dung, hot from the Hog, to the Bleeding Wound.”~Samuel Strangehopes, A Book of Knowledge in Three Parts (166[4])

Dubious medical device du jour - the prostate warmer.

Anoint the gums with the brains of a hare: advice from c. 1450 on soothing a teething baby.

Anoint the gums with the brains of a hare: advice from c. 1450 on soothing a teething baby.

Advice from 1380: How to Tell if Someone Is or Is Not Dead, with bonus Monty Python.

Urine-drinking Hindu cult believes a warm cup before sunrise straight from virgin cow cures cancer, baldness.

No comments:

Post a Comment