For William Wheatley's first production at the Continental Theater in Philadelphia, the decision was made to present Shakespeare's The Tempest (wiki) in ballet form. From England, Wheatley imported a special effects expert, as well as four ballet dancing sisters, the beautiful Gales – Ruth, Zela, Hannah, and Adeline. Six other chorus dancers rounded out the ballet troupe. On the night of September 14, 1861, the cast only made it through The Tempest’s first act.

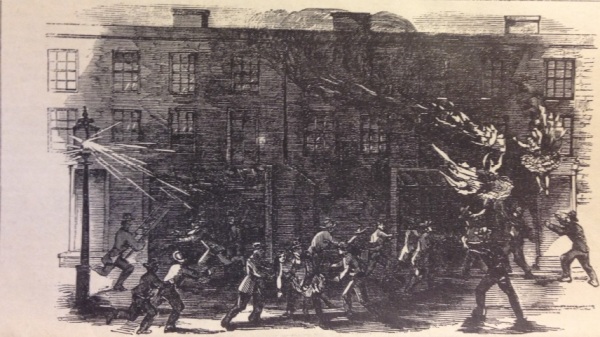

While the seas were raging at the end of the first act, the entire ballet company ran to change into gauzy costumes so as to be ready to welcome Alonso and the rest of shipwreck victims onto Prospero’s Island. At the Continental Theater the dressing rooms were above the stage itself, necessitating a fifty foot climb up a rickety flight of stairs. The chorus received their own dressing room, complete with lighting by means of gas jets close to the mirror, where their light could be reflected and doubled – if you look at the picture above, you’ll see the gas jets off to the top left.

|

| Flaming Ballerinas Plunging to their Deaths |

Above the mirror, Ruth Gale had hung her dress for the second act; she climbed onto the back of the couch to pull down her dress and the hem touched the gas jet. Instantly Ruth’s clothes were on fire, and as she ran screaming through the room, she set her sisters’ clothes on fire, as well.

Panicking, and on fire themselves, Ruth and her sisters plunged out the window and onto the street below, which was filled with pedestrians now under bombardment from flaming, screaming ballerinas who fell to earth with sickening thuds and the crack of broken bones.

Another member of the chorus, dress also ablaze, came running across the stage and fell into the pit where the stage crew simulated the storm that gave its name to the play. Tearing the cloths which represented the waves, they managed to smother the flames. Wheatley ordered the curtain brought down, and asked the audience to leave the theater peacefully. The remaining flaming ballerinas were extinguished.

Over the next four days, the six (one source says seven) ballerinas perished of their burns including all the Gale sisters. Wheatley was exonerated of any wrongdoing, and erected a monument to the perished ballerinas at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Philadelphia. The inscription on the stone is barely legible now, but the New York Clipper preserved it. It reads:

IN MEMORIAM

Stranger, who through the city of the dead

With thoughtful soul and feeling heart may tread,

Pause here a moment – those who sleep below

With careless ear ne’er heard a tale of woe:

Four sisters fair and young together rest

In saddest slumber on earth’s kindly breast;

Torn out of life in one disastrous hour,

The rose unfolded and the budding flower:

Life did not part them – Death might not divide

They lived – they loved – they perished, side by side.

O’er doom like theatre let gentle pity shed

The softest tears that mourn the early fled,

For whom – lost children of another land!

This marble raised by weeping friendship’s hand

To us, to future time remains to tell

How even in death they loved each other well.

|

| Maps: Top: 1858-1860 Middle top: 1875 Middle bottom: 1895 Bottom: 1922 |

Between the time of the fire described above and the end of the century, there were three additional fires at the same theater, although the name changed - on June 19, 1867, now known as Fox’s New American Theatre the group of ballerinas made it out safely and the audience was warned in time to leave the building. But, the front wall collapsed the onto volunteer firemen and others working along Walnut Street. As many as thirteen were crushed to death; at least four of them fire-fighters. The American Theatre was a complete loss.

The place was then rebuilt as the Grand Central Theatre (or just the Central Theatre) and suffered another major fire on March 24, 1888, a Saturday morning. No loss of life was reported, but the theater was, yet again, reduced to ashes. Plus, the stores and restaurants that faced Eighth Street from Walnut to Sansom were, once more, gutted.

Then on April 27, 1892, the yet-again-rebuilt Central Theatre was destroyed in a huge blaze that also devastated the adjoining Times newspaper office on Sansom Street, as well as the shops and eateries on Eight Street.

The audience members' exodus caused a stampede in which many were trampled underfoot. Those who lost their lives had ascended a stairwell that was one of two that led to doors in back of the theater, but unfortunately led directly to the fire itself. Confused when they found their escape route cut off, they were then overcome with fumes and died on the staircase. In a fit of hysteria, one man even forced his way out by slashing others with a bowie knife he had with him.

At least seven audience members and six performers died, and about fifty others were also hospitalized, suffering from excruciating burns and smoke inhalation. Some lost their eyesight, as their burns were mostly on the face. Many actors broke limbs when they jumped to the street from their dressing room windows onto Sansom Street, as the ballet dancers of 1861 had done.

|

| Gilmore’s Theater, the fifth and final playhouse at 807 Walnut | Image via The Roanoke Times, February 1893 |

What remained of the structure was torn down to allow for recovery of the bodies, and immediately reconstructed as Gilmore’s Auditorium. It opened on August 26, 1893, with architect John D. Allen setting it back five feet from the old building line and placing a turret on the roof in front. It was advertised as “Absolutely Fireproof” and “the safest and probably the best built theatre in this country.”

Perhaps it was absolutely fireproof, for the building did not burn again.

Via Hidden Philidelphia and Forgotten Stories.