Listen my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.

'Twas the eighteenth of April in seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

~ Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (wiki) Paul Revere's Ride, stanza 1)

The entire poem is at the bottom of this post.

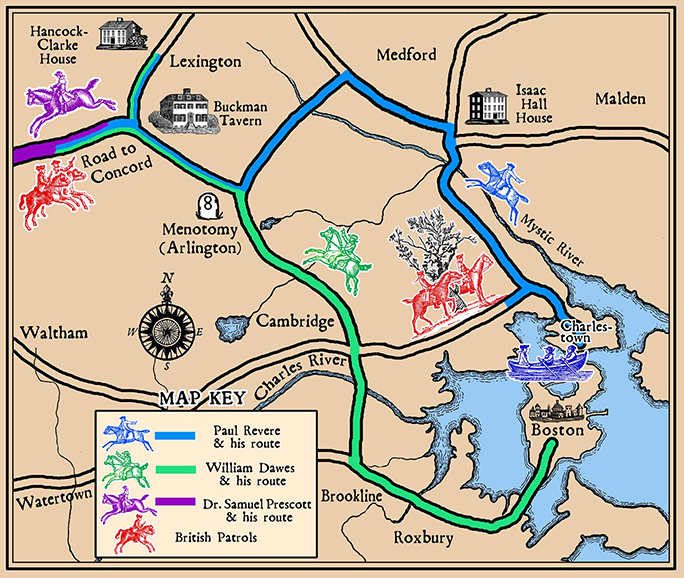

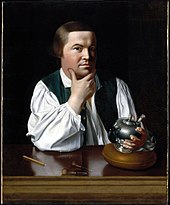

Paul Revere (wiki) gets all of the credit, but he never actually finished that famous ride, and in fact warned the British that the Americans were coming. William Dawes and Samuel Prescott were left out of the poem and subsequently most elementary history books: it was actually Samuel Prescott who completed the midnight ride.

Revere would be surprised that he ended up receiving sole credit for the midnight ride. In addition to Dawes and Prescott, dozens of other men helped spread the word that night. Revere started other express riders on their way before leaving Boston, and he also alerted others along his journey. They too began riding, or shot guns and rang church bells to alert the community.

Revere covered 13 miles in less than two hours, but he was not working alone. British patrols were posted along the roads, which is why more than one messenger was used for the mission.

Revere covered 13 miles in less than two hours, but he was not working alone. British patrols were posted along the roads, which is why more than one messenger was used for the mission.

In addition to omitting the efforts of Dawes, Prescott and dozens of nameless midnight riders, Longfellow's poem contains other errors as well; most notably, the signal of two lanterns hanging in the Old North Church was a signal from Revere, not a signal to Revere. In his defense, Longfellow didn't intend for the work to be an historical account - the 1860 poem was meant to inspire his countrymen on the eve of the Civil War.

|

| Click to embiggen. |

Here's William Dawes' story:

I am a wandering, bitter shade,

Never of me was a hero made;

Poets have never sung my praise,

Nobody crowned my brow with bays;

And if you ask me the fatal cause,

I answer only, "My name was Dawes."

|

| William Dawes |

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere;

But why should my name be quite forgot,

Who rode as boldly and well, God wot?

Why should I ask? The reason is clear --

My name was Dawes and his Revere.

When the lights from the old North Church flashed out,

Paul Revere was waiting about,

But I was already on my way.

The shadows of night fell cold and gray

As I rode, with never a break or a pause;

But what was the use, when my name was Dawes!

History rings with his silvery name;

Closed to me are the portals of fame.

Had he been Dawes and I Revere,

No one had heard of him, I fear.

No one has heard of me because

He was Revere, and I was Dawes.

~ Helen F. Moore (1851-1929) ("The Midnight Ride of William Dawes," Century Magazine, 1896)

As every schoolchild knows, Paul Revere's ensuing midnight ride called the local militia to arms, and the battles of Lexington and Concord followed the next day. Largely obscured by the great renown of Longfellow's poem, "Paul Revere's Ride" (included in his Tales of a Wayside Inn of 1863), is the fact that two other men - William Dawes (1745-1799) and Dr. Samuel Prescott (1751-1777) - also rode that night to spread the alarm. Moreover, it can be argued that Revere was the least successful of the three, because although he and Dawes were both captured by the British, Dawes escaped to arouse Lexington, and then Prescott carried the word to Concord.

For some, the midnight ride conjures images of Paul Revere riding through the night, shouting out, "The British are coming! The British are coming!" But this phrase would have made no sense to the colonists; everyone at that time thought of themselves as British. Instead, Revere spread his message subtly by saying something along the lines of, "The Regulars are coming." The troops were known as Regulars, Redcoats or The King's Men. The troops called the colonists country people, provincials, Yankees, peasants or rebels.

Here's Longfellow's entire poem:

|

| Paul Revere |

Listen my children and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, "If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch

Of the North Church tower as a signal light,--

One if by land, and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country folk to be up and to arm."

Then he said "Good-night!" and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

Meanwhile, his friend through alley and street

Wanders and watches, with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers,

Marching down to their boats on the shore.

|

| Old North Church |

Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church,

By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread,

To the belfry chamber overhead,

And startled the pigeons from their perch

On the sombre rafters, that round him made

Masses and moving shapes of shade,--

By the trembling ladder, steep and tall,

To the highest window in the wall,

Where he paused to listen and look down

A moment on the roofs of the town

And the moonlight flowing over all.

Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead,

In their night encampment on the hill,

Wrapped in silence so deep and still

That he could hear, like a sentinel's tread,

The watchful night-wind, as it went

Creeping along from tent to tent,

And seeming to whisper, "All is well!"

A moment only he feels the spell

Of the place and the hour, and the secret dread

Of the lonely belfry and the dead;

For suddenly all his thoughts are bent

On a shadowy something far away,

Where the river widens to meet the bay,--

A line of black that bends and floats

On the rising tide like a bridge of boats.

Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse's side,

Now he gazed at the landscape far and near,

Then, impetuous, stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry tower of the Old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry's height

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet;

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.

He has left the village and mounted the steep,

And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep,

Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides;

And under the alders that skirt its edge,

Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge,

Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides.

It was twelve by the village clock

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer's dog,

And felt the damp of the river fog,

That rises after the sun goes down.

It was one by the village clock,

When he galloped into Lexington.

He saw the gilded weathercock

Swim in the moonlight as he passed,

And the meeting-house windows, black and bare,

Gaze at him with a spectral glare,

As if they already stood aghast

At the bloody work they would look upon.

It was two by the village clock,

When he came to the bridge in Concord town.

He heard the bleating of the flock,

And the twitter of birds among the trees,

And felt the breath of the morning breeze

Blowing over the meadow brown.

And one was safe and asleep in his bed

Who at the bridge would be first to fall,

Who that day would be lying dead,

Pierced by a British musket ball.

You know the rest. In the books you have read

How the British Regulars fired and fled,---

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard wall,

Chasing the redcoats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

So through the night rode Paul Revere;

And so through the night went his cry of alarm

To every Middlesex village and farm,---

A cry of defiance, and not of fear,

A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door,

And a word that shall echo for evermore!

For, borne on the night-wind of the Past,

Through all our history, to the last,

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

The Revolutionary War began the next day - April 19, 1775. Here's Emerson:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled;

Here once the embattled farmers stood;

And fired the shot heard round the world.

~ Ralph Waldo Emerson, Concord Hymn (stanza 1)

Remember the kerfuffle when Sarah Palin mentioned that Revere actually told the British that the Americans were coming and the "intellectuals" on the left, who got their history from the poem, made much of what an idiot she was?

|

| Revere captured by Regulars (source) |

I observed a Wood at a Small distance, & made for that. When I got there, out Started Six officers, on Horse back, and orderd me to dismount;-one of them, who appeared to have the command, examined me, where I came from, & what my Name Was? I told him. it was Revere, he asked if it was Paul? I told him yes He asked me if I was an express? I answered in the afirmative. He demanded what time I left Boston? I told him; and aded, that their troops had catched aground in passing the River, and that There would be five hundred Americans there in a short time, for I had alarmed the Country all the way up. He imediately rode towards those who stoppd us, when all five of them came down upon a full gallop; one of them, whom I afterwards found to be Major Mitchel, of the 5th Regiment, Clapped his pistol to my head, called me by name, & told me he was going to ask me some questions, & if I did not give him true answers, he would blow my brains out. He then asked me similar questions to those above. He then orderd me to mount my Horse, after searching me for arms. He then orderd them to advance, & to lead me in front. When we got to the Road, they turned down towards Lexington. When we had got about one Mile, the Major Rode up to the officer that was leading me, & told him to give me to the Sergeant. As soon as he took me, the Major orderd him, if I attempted to run, or any body insulted them, to blow my brains out. We rode till we got near Lexington Meeting-house, when the Militia fired a Voley of Guns, which appeared to alarm them very much.

Further reading:

There's an excellent breakdown at the Journal of the American Revolution's blog: Dissecting the Timeline of Paul Revere’s Ride, and this article at the same publication is also worthwhile: How Paul Revere’s Ride was Published and Censored in 1775.

PaulRevereHouse.org's article on the real story has an interactive map.

PaulRevereHouse.org's article on the real story has an interactive map.

HowStuffWorks: What happened to the two other men on Paul Revere's ride?