Are the men that God made mad,

For all their wars are merry

And all their songs are sad.

~ G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) (Ballad of the White Horse* (wiki))

My personal favorite Irish joke:

Some of the stories and traditions associated with Saint Patrick (wiki) are actually probably from another man that preceded Patrick by a 1-3 decades (exactly how much isn’t known), Palladius. It has also been argued by some scholars that the blending of these two’s accomplishments was done purposefully to bolster the prestige of Saint Patrick. Palladius was one of the earliest missionaries to Ireland, ordained by Pope Celestine the first as the “First Bishop to the Irish believing in Christ”. However, accounts seem to indicate the Palladius and his companions’ mission was fairly unsuccessful and Palladius himself was eventually banished by the King of Leinster, at which point he went to Northern Britain to preach to the Scots. Nevertheless, much of what Palladius did accomplish while in Ireland has long since been credited to Saint Patrick instead and it’s difficult to tell in most cases exactly which of them accomplished what.

For all their wars are merry

And all their songs are sad.

~ G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) (Ballad of the White Horse* (wiki))

Sir... the Irish are not in a conspiracy to cheat the world by false representations of the merits of their countrymen. No, Sir, the Irish are a FAIR PEOPLE; - they never speak well of one another.

~ Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) (Boswell's Life of Johnson, 1775)

|

| St. Patrick with a shamrock - more on the shamrock connection here. |

The 17th of March is St. Patrick's Day (wiki), commemorating the patron saint of Ireland, Padraig mac Caiprainn (ca. 390-461?). Much of Patrick's life is shrouded in legend, but he is said to have been born in Roman Britain and was captured and enslaved by Irish raiders until he managed to escape to Gaul. There, he entered the priesthood but returned to Ireland as a missionary and made many converts, reportedly by using the leaves of the shamrock to explain the three-in-one mystery of the Trinity.

In 445, with the approval of Pope Leo the Great (reigned 440-461), he established his arch-episcopal see at Armagh, and by the time of his death, Ireland was largely Christianized. Our principal source about St. Patrick's life is his own Confessions, written in his last years.

"An Irishman walked out of a bar... " (that's all of it).

The story of St. Patrick:

King George III in 1783 created a “Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick”, which is an order of knights of Saint Patrick given to certain people associated with Ireland who the monarchy wishes to honor. It’s been decades since the last person was inducted into this order and the last person in the order died in 1974, Prince Henry the Duke of Gloucester. Nevertheless, the order still technically exists with the Queen functioning as the Sovereign.

For St. Patty's Day: Excellent Drinking Stories. And here's how to make your own green beer.

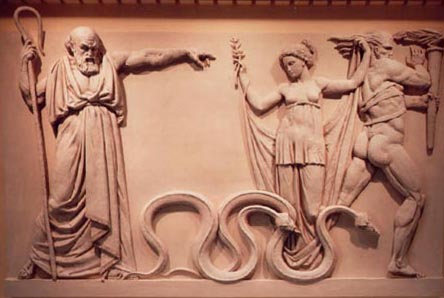

Saint Patrick, Druids, Snakes, and Popular Myths explains the pros and cons of the theory that the “snakes” that Patrick drove out of Ireland were the Druidic priests, who had serpents tattooed on their forearms.

Based in part on a post at the excellent Today I Found Out (their Wise Book of Whys has gone to several family members as presents).

The epic poem Ballad Of The White Horse (link is to a free Kindle version) tells the fascinating story of Alfred the Great's stand against the Danes in 878 - or read about the subject at Wikipedia. Per Amazon:

More than a thousand years ago, the ruler of a beleaguered kingdom saw a vision of the Virgin Mary that moved him to rally his chiefs and make a last stand. Alfred the Great freed his realm from Danish invaders in the year 878 with an against-all-odds triumph at the Battle of Ethandune. In this ballad, G. K. Chesterton equates Alfred's struggles with Christianity's fight against nihilism and heathenism—a battle that continues to this day.

One of the last great epic poems, this tale unfolds in the Vale of the White Horse, where Alfred fought the Danes in a valley beneath an ancient equine figure etched upon the Berkshire hills. Chesterton employs the mysterious image as a symbol of the traditions that preserve humanity. His allegory of the power of faith in the face of an invasive foe was much quoted in the dark days of 1940, when Britain was under attack by Nazis.